Cricketing Memories by David Alexander

The rain beat down on the roof of the pavilion and flooded the playing field stretching before me. Lightning cracked and thunder rolled as I stood, not three foot high, in the doorway fascinated by this display of the wrath of the gods but not in any way fearful because there was the reassuring figure of my father, his striped blazer hitched over his head against the storm, running from the changing hut to join me on the pavilion steps. I felt quite safe as he drew me into shelter and bought me a tuppenny packet of Smiths Crisps with its blue twist of salt to allay the anxiety which he felt I must be experiencing

This is one of my earliest memories and the beginning of a lifelong devotion to the game of cricket. It was also an experience which was to be repeated umpteen times as the years went on – that dismal prospect of a game washed out by a storm and twenty two despondent cricketers doing their best to be optimistic about the likelihood of a resumption of play. Not even a packet of crisps could compensate for the disappointment of a looming abandonment of the day that had begun so promisingly. However, there were the sandwiches to be eaten, the pin-ball machines to be played, the gear to be repacked and loaded onto the rear luggage rack of the Morris Minor and the long journey back to Dulwich to be enjoyed as the fixture list was scanned with my elder brother to anticipate the date of the next encounter.

That match, which has lain so long in the memory, was probably at Alperton, which figured for several years in the fixture list of the Surrey Pilgrims, the wandering club that was run by my father as Secretary/Treasurer before WW2. The year would have been about 1929 and there stretched from that time a happy succession of seasons when almost every week-end would find us chewing grass at the boundary’s edge or sitting at the elbow of Mr Green, our immaculate scorer, at one cricket ground or another around London. My mother was the faithful follower and provider of refreshment; my brother and I were the keepers of the scoreboard and occupiers of the practice nets in our endless games of small cricket. My recollection is that I spent most of my time bowling at him and only occasionally was I permitted to bat. But that may well be a distorted memory born of sibling rivalry. Indisputable was the fact that he was a much better cricketer than I. I do remember being pleased with myself for being pretty agile in the field. We acquired a rubber ball to practice fielding and catching which was called a Googly Ball. It had a harder ring of rubber which made the bounce quite unpredictable and it was an excellent tutor for quick reactions. I wonder whether one still exists somewhere in the bottom of a long and ancient leather cricket bag.

Certainly those were halcyon days in the company of the lions of the Surrey Pilgrims, all of them connected with local government or civil engineering and some good cricketers amongst them. They would coach us while waiting to bat and impart those essentials of cricketing lore to us aspiring juniors. There did come the day in the last summer before war broke out when I was allowed to fill in for some late drop-out in a match down the Foots Cray Road against an insurance company and I took guard with the greatest pride at the age of fourteen and scored a couple before being bowled neck and crop!

One of the great delights of those pre-war summers was to take a packet of sandwiches and a bottle of Tizer and occupy a seat in the free stand at the Oval or Lords. I either went alone or with my good friend Jim Breese who lived by the park gates on Dulwich Common. Jim was so keen on cricket that his father installed a cricket net in the back garden for summer practice and in winter we used to play a complicated game of small cricket in front of the garage – four if you hit the flower pots and six if you connected with the drain pipe. But it was those days with Middlesex or Surrey which cemented my infatuation with the game. Hobbs and Sutcliffe, Fishlock and Gover, Tyldesley and Hammond, Hutton and Washbrook, Larwood and Voce, Wellard and Sims – the names ring across the years and their exploits with bat and ball remain undimmed in the memory. Arthur Wellard even played for the Surrey Pilgrims in his latter years and I clearly recollect his huge figure lifting the ball effortlessly over long on for successive sixes at Crofton Park or perhaps it was Croydon MOs overlooking the old Croydon Airport.

My father was acquainted with several members of Surrey County Cricket Club and I was often fortunate enough to get into the Pavilion where I would occupy a seat in the single row right at the top from where they now televise the games. At the end of a session I would tear down the stairs to the flight leading to the players’ dressing rooms and accost the passing god-like figures for their autographs. It was from the same pavilion that I saw Bradman score a century before lunch. I still have those autograph books, the larger one with complete teams inscribed in the dressing rooms, the smaller one with individual signatures, some of them defaced by the scribbling of my younger brother’s infant hand. How could anyone scrawl over the hallowed autograph of Harold Larwood? Sacrilege!

School cricket was taken pretty seriously at Alleyn’s School in Dulwich. Matches were played at House level and School XIs were fielded at Under-13, 14, Second XI and First XI. A professional (Mr Brown of Surrey, I believe) was employed for coaching and much net practice was insisted on if you had aspirations to a School XI. On one occasion I remember cutting net practice to go to Wimbledon. My father was aghast at this disloyal behaviour and gave me no end of a wigging. I suppose I was reasonably adept at the game and certainly keen but I am sure I would have benefited from more expert coaching. Mr Brown was mainly engaged with the First and Second XIs. Notwithstanding, I progressed to captain the School Under-14 XI in 1938 and much enjoyed being let off school to visit our opponents in South London and as far afield as Ardingly. In 1939 I played in a few matches for a strange Under 14½ XI and for the School Second XI but was not senior enough or skilful enough to be picked for the First XI. That honour was reserved for brother Lindsay who was a very useful bat and received his First XI colours before he left at the end of the 1939 season. It was the greatest pity that his busy life never enabled him to play seriously again, although I believe he played for some Army XI on the Test Ground at Durban on his way to the Middle East.

In 1940 I was picked for the First XI games which were arranged during our evacuation to Maidstone and continued to play regularly through the following two years when we were sharing with Rossall School north of Blackpool but, despite 2½ years in the XI, I was not awarded my colours. The Cricket Master was seized with the notion of ‘maintaining pre-war standards’ and, combined with the rather supine attitude of the Captain, it was enough to deny me what I felt were my just deserts! I was pretty mortified at the time but was much comforted by my particular cronies in the XI, Roger and Bruce Farthing, who thought I had been hardly done by. In any case it was a huge delight to meet and play against the prestigious schools in the North West like St Bee’s and Stoneyhurst and the matches against Rossall were always needle encounters. The Rossalians always felt superior to the ‘yobbos’ from London but we did succeed in showing that we could play cricket even if we did play plebeian soccer rather than rugby.

Once I had joined up in 1943 I did not have the opportunity of playing until I was demobilised in 1946. Even at Oxford I played no cricket. The College side at that time was very strong with numerous blues and all the ex-service men up at the same time. I would not have got a look in. In addition I had elected to accept the offer to ex-servicemen of taking a shortened two-year degree and the amount of reading for the English School was such that I felt I could not spare the time. It was a stupid decision which I much regret and I am sure in retrospect that it would not have made the slightest difference to my degree if I had joined the very informal college side called the Hornets which played evening matches against the surrounding villages – in addition to sinking a powerful quantity of beer. It would have been a wonderful relaxation and escape from Beowulf and The Faerie Queen!

They really were happy family days on which I look back with great nostalgia. For an all-day game they really began pretty early. The baby had to be fed and breakfast eaten before loading the mini-van with picnic and nappies, pushchair and cricket bag. Mustn’t forget the team list or the gleaming new match ball or the soft ball for the kids; hats and rainwear (just in case); my beautiful buckskin pads (later nicked at Lords Indoor School by some covetous cricketing predator – I hope he made better use of them than I usually did); and lastly try not to leave the baby behind in the flat in his carry cot, which had been known to happen! Then the swift run through the suburbs to one or other of the delightful grounds outside London where old friends were gathering and deckchairs were being bagged for the wives and families

Some years after I had come down from Oxford, Ian Crombie (a Harrods friend of brother Sandy’s) introduced me to the Nomads Cricket Club. I had not played for years and I was apprehensive about my likely performance. The club was run by Sidney Caulfield who had joined with other architects and Oxbridge graduates in forming it as the Hampstead Nomads in 1903. He was a cricket fanatic of advanced years and bachelor habits who patrolled the boundary at every match, peering out from beneath his tweed hat and launching unmerited applause or sharp criticism of the players whom he dimly saw with his fading eyesight flickering in the distance against the elms or the setting sun. He was reputed never to sit down. He umpired for many years until his glasses were smashed into his face by a throw from cover point which he failed to see. He was carted off to hospital but recovered sufficiently to stand again three or four weeks later. However, after a few more than usually outrageous decisions, he did admit that he could not distinguish the ball from the cloud of other black specks advancing towards him and he was persuaded that for the sake of maintaining our fixture list it would be best if he retired permanently to the boundary. I am sure that his tweed-clad shade lurks still in the long grass at Epsom or Esher, muttering words of praise or blame. But where would the game of cricket be without the devotion and idiosyncrasies of such as Sidney Caulfield?

At that first game played for the Nomads against Chalfont St Peter I was fortunate in two respects. First, I managed to glance a leg-side ball for four in my first over and, secondly, Sidney actually observed the fortunate contact and thereupon pronounced me a player that the club must retain. It also helped that I had been in the Indian Army and had been to Oxford. He was a terrible snob. But my future was assured and I played for the Nomads for the next fifteen or twenty years, eventually succeeding as Secretary and President. I now bask in the golden glow of being President Emeritus – although few know just how little I deserve that sublime appointment and how much it is due to Sidney’s poor eyesight!

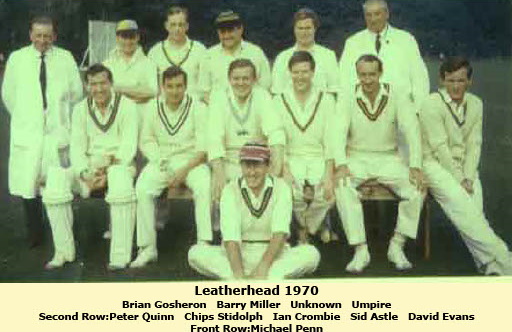

Rudgwick was one of our favourite fixtures where once we assembled 13 children of the Nomads tribe. The number of children seemed to increase match by match. At Four Elms they made such a racket dashing round the boundary that complaints from the more staid supporters of the home side led to our losing the fixture. Then there was Beaconsfield where a nameless Nomad, having carted the ball to all parts, returned to the pavilion to declare, ‘That was the worst century I have ever scored’! At Oxford and Cambridge we played on some of the best wickets in our fixture list: New College and Worcester, Queen’s and Clare. Something of a contrast to the meadow at Pickersgill but although the pitch there may have been hostile the opposition was of the friendliest: John Gold, Paul Maloney and the great John Nagenda amongst them. But it was the game at Leatherhead that perhaps stays longest in the memory. It was traditionally the last fixture of the season and something of a gala occasion, played often in the first week of October. One had first to sweep the frost off the wicket and then don two if not three sweaters against the cold. The cricket was light-hearted and lunch an extended affair at which the wine flowed, speeches were made and toasts drunk. The humour became more hilarious as the wine intake increased and even eight year-old Greg was found on one occasion very much the worse for wear having downed the odd glass or three! As dusk fell and the mist gathered over the last obsequies of the season, we piled into our cars, said our farewells until next year and weaved our unsteady ways home, quite a bit happy or sound asleep according to age. Why we were not all stopped by the police I will never know. I was stopped once having drunk ourselves back into next year’s fixture after a bad loss at Westerham and merely advised to ‘Drive quietly back home, if I were you, Sir’. Things were so much more civilised in those days.

What other names rise to the surface of Nomads memories of those post-war days? Certainly topping the list is ‘Granny’ Alston, one of the most faithful Nomads. He was a very private man, living alone, gruff of speech and of few words but no mean cricketer. A crafty slow bowler (with a habit of spinning the ball on the back of his hand between deliveries) and a most useful bat who whipped the ball off his pads to the leg-side boundary in a manner of which Pietersen would be proud. He had played for Somerset Second XI in his younger days and with the Nomads made the most statuesque and immobile gully fielder I have ever met. But no-one who was present will forget him going out to bat at the P&O ground with 12 year-old Charles Penn – 60 years between their ages.

Then there was John Nagenda, the genial Ugandan who played for East Africa in the first World Cup at Lord’s: a quick bowler of renown and a powerful bat who could turn a game round in the space of a few overs. Nor shall we forget Colin Owen-Browne whose enthusiasm and vigorous performance as captain and all-rounder did much to revive the fortunes of the Club when they were at a low ebb in the seventies. Other stalwarts were Ian Crombie whose eccentric slow bowling often surprised himself as well as the opposition; ‘Chips’ Stidolf who managed to keep wicket and bat with a prosthesis on his right arm; Alick Moore whose admin skills as Secretary were matched by his amiable personality and his skilful off-spin; Colonel Roy Wright who thundered up to the wicket to deliver his quick-medium military seamers; the elegant David Evans; the energetic Mike Ghersie; Tony Whiteway the most tenacious bat of all time; John Gold behind the stumps; Mike Fermont; Mike Wilkins; brother Sandy; nephews Patrick and Charles – the names roll onwards from the shadowy past and all made their contributions to the ethos and the success of the Nomads as a wandering side for whom it was a pleasure to play.

In truth, I was never a great performer with the bat and could not bowl for toffee-nuts. But I enormously enjoyed the game and the friendships which it brought. Someone had to do the management after Sidney died and Alec Moore and ‘Chips’ Stidolph (his immediate successors) moved on. So I spent my winters assembling the fixture list and my summers cajoling players to make up the elevens week after week. I never made a host of runs myself but, as an opening bat, managed to stay at the wicket for a reasonable time to see off the quick bowlers and lend some respectability to the early overs of our innings. In any case it was enough to smell the new mown grass and sprint round the third man boundary. It was a great relaxation from the pressures of a city solicitor’s life to vegetate in the outfield and applaud the performance of others.

However, my scuttling on the boundary was my downfall on one occasion. We were touring in Belgium and playing on a matting wicket. We were therefore required to wear spikeless footwear lest we tore the matting. There had been rainfall overnight and the outfield was very damp. I attempted to cut off a shot to third man with my usual reckless commitment but as I braked my feet shot from under me and I landed on my left wrist. There was a sickening snap which echoed round the ground and I found myself nursing a very misshapen left wrist. My solicitous nephew Patrick rushed over to give comfort and I was shipped off to hospital to have the break set by a pretty incompetent Belgian doctor. The plastering was done far too tightly and by the time I arrived back in England my hand was going blue and I had to resort to a local orthopaedic surgeon (who happened to be an Indian) who inspected the damage and then uttered, in a strong Indian-English accent, the immortal phrase, ‘Well, what can you expect from these Common Market doctors!’

It was not at all easy to run such a wandering side as the Nomads (we had no ground of our own) and filling sides week after week became increasingly difficult. While we had some recruits from itinerant Aussies and South Africans and from the resident West Indian population, much of the young cricketing talent was at that time being recruited into good London and Home Counties sides that were beginning to form the leagues which became so popular. It was not until I relinquished the Secretaryship that the flood of immigrants from all over the Commonwealth made life much easier and improved the standard of our cricket. Now the fixture list has expanded, there are several overseas tours every season and, with Michael Blumberg as Secretary/President, the Club flourishes as it has never perhaps done before. No more the frantic round of telephone calls on a Friday night pleading with occasional players to turn out at some outlandish village in Hampshire at 11.30 the next morning. Good players in their middle years have dropped out of the pressure pot of league cricket to play our more relaxed style of the game and youngsters from the Indian, Pakistani and West Indian communities here are anxious to be available.

My last game for the Nomads was against Merrow in Surrey and it was a paradigm of the fascination which cricket continues to exert on its devotees. Merrow, a village satellite of Guildford, had always been one of our pleasanter fixtures. It was a rural ground on a slope, with a modest wooden pavilion and hospitable hosts. We fielded first and bowled them out for a reasonable but not unachievable score. My triumph of the afternoon was to throw down the wicket from cover point to run out one of their more prolific batsmen – a feat which I do not remember having done before. It was a moment of high elation. Our performance with the bat was not much better than theirs and by the time I went in low in the order we were in some difficulty in reaching their total. However, I was still in with the last wicket to fall and we needed only two to win. Thinking to cover myself with even more glory, I attempted to reach the mid-wicket boundary with a massive ‘hoik’ to leg. Of course I put the ball straight down the throat of mid-wicket and we lost by a couple of runs. Glory turned to ashes! Oh so typical of the great game but perhaps a very fitting way to end my modest cricketing career. As I recall, Gina, who was present on the boundary as she so often was, failed to see either incident. But I have to give her due praise for following the Nomads so faithfully over the years, as, willy-nilly, did my sons Greg and Tristram. But then she did open the bowling for her school and watched Trevor Bailey bore for Essex at Chelmsford with her father, so perhaps her interest had been stimulated long before I appeared on the scene

My association with the Nomads continued and after I handed over the Secretaryship to Michael Blumberg I was elected as President, a position which I was pleased to hold for twenty years or more before being elevated to the stratosphere of‘ President Emeritus’. As President I did try to attend as many Committee Meetings as I could but I fancy that my chief duty was to deal with a few instances of bad conduct on or off the field and occasionally to bail out the club when it got into financial difficulties or a Match Manager absconded with the match fees. I am delighted that the Nomads have not only survived past their centenary but are continuing to flourish. Now my undiminished love of the game is confined to watching Test Matches at Lords (where I am fortunate to be a member) or on the TV where Sky provides an endless flow of cricket from all over the world: test matches, 50 over one-dayers and even the new and successful 20/20 competition. It is still a thrill to see skill and courage combine to force a glorious victory or rescue an apparently hopeless situation. Cricket seems to me to be a game which exemplifies much of what I see to be the virtues of life: good fellowship, loyalty, the ability to work well with others, physical skill, determination,psychological insight to read the game and the strengths and weaknesses of your own players and the opposition, and the will to win but not at the expense of good natured behaviour and good manners. A bit old fashioned? Well so be it. Sledging was pretty well unheard of and we did actually ‘walk’ when we knew we had nicked a catch to the keeper.Perhaps it is all summed up in the following anonymous lines entitled ‘An Old Man Dreams’ which are included in that marvelous MCC anthology of cricket verse,

‘A Breathless Hush…’An old man by the fire will dream